I am preparing a series of stories of people who find themselves adrift in the water. The first story comes from an incident that occured in August 2002 whlile I was on the live aboard diveboat, the Undersea Hunter, in August 2002. It is purely coincidental that this story appears on Mother's Day 2024.

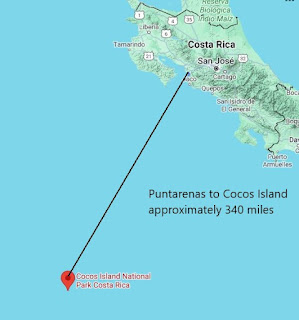

To say that Cocos Island, Costa Rica, in the Pacific Ocean, is "isolated" is an understatement. The island, designated Cocos Island National Park, lies approximately 340 miles southwest of the Costa Rican mainland. “Middle of nowhere” barely begins to describe

this location. Just getting to the island required a 30+ hour boat ride from

Punta Arenas on board Undersea Hunter—a

top live-aboard dive boat. I was

traveling with a group organized by Brandon and Melissa Cole. Our group claimed many of the available

spaces on the boat; others took the rest.

I had prepared for the remoteness of the location by

incorporating into my dive gear, in addition to the whistle permanently affixed

to my buoyancy compensator, an extremely loud surface signaling device powered

by the compressed air (from my tank), a bright green surface marker buoy, a

flashing strobe light and a signal mirror.

I had considered a bright green dye marker pack, but the container could

not sustain the pressure of deep water immersion without hemorrhaging the dye.

Diving

Safety Briefing

The first predive briefing of the trip, held prior to our

first dive, emphasized the conservation orientation of the operators at Cocos

Island and what a privilege it was to dive in this unique marine wilderness. (Only park personnel and scientific

researchers are allowed on shore.) The “boat rules” include no intentional

interaction with the fish, no feeding of fish, no manta riding, and no pulling

the shark’s tail. One would think these

rules need not be explicitly stated given the conservation ethic of

diving. My observation of diver

behaviors over the years is to the contrary.

When in doubt, point it out.

The second half of the briefing emphasized safety and the

need to follow the diving protocols. Divers

were directed not to exceed the 130 foot depth limit. The briefer noted that divers were

responsible for knowing and not exceeding their individual “no decompression

limits. Other protocols emphasized the

need to maintain visual contact with the underwater walls. Also, since the dive spots are fairly deep,

the divemaster highlighted the need to complete the safety stop for three

minutes between 15 and 20 feet during ascent with one exception.

“No blue water diving!” the divemaster stressed. “If you

cannot see the wall or if you are in a strong current; do not do the

three-minute safety stop! Surface immediately, inflate your bc and marker buoy and the tender

will pick you up. The current will carry

you away from the island and the nearest landfall Is Antarctica.” It is a lesson we learned later that day.

The

Second Dive

Our second dive ended as a cautionary tale about diving

in the current. We planned to drop in on

the southwest side of Isla Manuelita, and descend as a group along the step

down slope to between 60 and 100 feet, while moving north. The orientation to do that is to keep the wall

on the right hand side. We would round the end of the islet and be picked up on

the northeast side.

After a routine descent, the divers wedged themselves

into a ledge along the wall to await the appearance of hammerhead sharks. I ascended a bit to address an issue and

found myself surrounded by fish. I could

not get back to the main part of the group as I was up current of their

location. Rather than fight against the current, I continued the dive. I had done a number of drift dives over the

years so I was comfortable doing so. The

current pushed me along the wall. I am able to maintain visual contact with the

wall. I start my ascent upon reaching my

“low air” tank pressure of 700 psi. After completing the three-minute safety

stop, I surface. The panga motored over

to retrieve me, as the current kept me from swimming to it. I am the first one on board.

Mom

goes adrifting

The group had spread out along the wall, with the

photographers bringing up the rear. As

the panga retrieved the divers, a diver returned onboard without her

buddy. The buddy pair, a mother-daughter

duo, is missing the mom. The daughter

reports that they were in a current as they ascended. The mom was carried out into blue water and

continued with the safety stop while the daughter surfaced. She did not see her mother surface.

A search immediately commenced. We cruised along the current line looking for

any sign of the diver, but we found nothing.

Visibility decreased as a squall line moved into the area. The divemaster’s initial look of optimism at

finding her quickly changed to one of consternation. He alerts the mothership by radio to dispatch

the second panga to join the search as soon as their divers are recovered. The Park Ranger from the island joined the

effort from his skiff.

Time passed. All

eyes on our panga desperately scan the water for a sign of the diver. We searched for what seems like an eternity

moving back and forth along the current line.

Suddenly, the radio sounded. The

other tender reports they have recovered the diver on the surface. We race over to their location, relieved that

the mother is OK.

Back on board the Undersea Hunter, the divemaster asked the

mother what happened. She replied,

“since it was a deep dive, I felt making the safety stop for the three full

minutes was very important.” She insisted

that nothing was wrong, seemed unfazed by the whole experience and appeared oblivious

to how close she came to going missing.

After a discussion that focused on the critical importance of directly

surfacing when in blue water, the incident is closed. But, the lesson stayed with us for the rest

of the dives.

No comments:

Post a Comment