Diving with Francisco!

We arrive at Puerto Escondito at ten minutes before seven eager to go diving. The day was going to be clear and warm and the Gulf had a lake-like flatness--perfect dive conditions. Francisco is ready. We quickly loaded the panga.

I turned and told the guys I wanted to lock the truck before we left. Francisco informed me that doing so was not necessary and seemed a little disappointed that I assumed it would be. We got underway, only to stall just outside the port. Another panga motored up beside us and Francisco and the other skipper diagnosed and fixed the problem. We were underway again headed toward Submarine Rock, so named because of the islet’s resemblance to a sub with decks awash with its central rock stack forming the conning tower. With a little imagination you can almost hear a claxon with the captain’s voice calling "dive, dive, dive" over the loud hailer. And dive is what we came to do!

At Francisco’s signal Brandon dropped the anchor, a large rock secured by a rope cradle. We geared up and shortly after 8 a.m. we back rolled off the panga on the count of three, Andy and Brandon on the other side of the panga me on the other, with Franciso shifting his position to act as a counter balance, lest the narrow-beamed panga tilt too far to one side or the other and flip over.

We dropped down to 40 feet and for the next hour were treated to a variety of fish, including the ever present sergeant majors and angel fish, with a great abundance of scallops and oysters. When my pressure gage shows 500 p.s.i. of air remaining in the tank, I leave my two buddies and make my way back to the panga. I hand my weight belt to Francisco. I roll out of my buoyancy compensator. Francisco grabs the tank valve and hauls the tank-b.c.-regulator rig into the boat before positioning himself on the opposite side of the boat so I can grasp the edge of the boat and pull myself over the freeboard. The boat tilts toward me, responding to the laws of physics. I outweigh Francisco by at least 100 pounds. As I flop onto the floor of the panga, he returns to fishing with a handline. We converse in broken Spanglish, with Francisco knowing more of my language than me of his. I manage to convey that Brandon is a student at the University studying marine biology and that Andy is an engineer.

We recover the remaining two divers and motor over to La Islette de las Tigerous. We flawlessly execute our back rolls, we seem to be getting pretty good at it with all the practice that we had. The dive lasts 47 minutes, which takes us pretty close to our no decompression limits as we figure them using the NAUI dive tables.

The terrain is large boulder wall, much like a breakwater but much deeper. Visibility is great, about 60 feet. In spite of the great vis, I am a bit disappointed at the start of the dive due to be bleakness of the area. First impressions are not accurate as the area rapidly changes character. We see several large groupers, countless sergeant majors, king angel fish, and what looks like the crown of thorns starfish.

The dive is fabulous, but it ends too soon, as my strict

adherence to the 500 p.s.i. rule and the minute hand on my black-faced Seiko

automatic dive watch conspire to bring us to the surface. We ascend slowly,

moving up slope, probing the crevices and savoring everything the spot has to

offer. The sea seems to call, "wait! don’t go...I have more to show you.

Explore more for the wonders the area. If you leave now, you may never be back

this way again. Look under the ledge at the scallops hanging in the current

like so many salamis hanging in a butcher shop window. Over there! Over there,

is that a black sea bass?"

Back in camp we have the rest of the afternoon off. Brandon

announces he is going snorkeling and I decide to tag along. Brandon is a

nudibranch afficionado and scholar. I recall from the Log of the Sea of Cortez

that while collecting from a tidepool "Doc" Rickets wondered what the

critter tasted like. He plucked one out of the water and popped it in his mouth

in what can only be described as empirical research, that which we know from

our five senses. I wanted to be there if Brandon decided to replicate the

experiment.

We move toward the south end of the bay where a small islet sits off the point. As the crow flies, the distance is short, but our circuitous route we take meanders along the shoreline, in and out of the numerous channels. One inlet has many marine caves, which we swim into, only to discover they go some distance back. Brandon points out a puffer fish that is nearly fully inflated. While this species is numerous in the area, this is the first that I have seen blown up into a ball with fins. I wonder what caused it to inflate, which I am given to understand is a defense mechanism. Moving out of the channels we see rays streaking from under the sand and scooting across the sand bottom in what seems to be an aquatic game combining "hide and go seek" and "tag." We watch these antics as we kick across the bay to an exit point near camp. After two hours kicking, I am looking forward to a good night’s sleep. I light my propane backpack stove to boil water for a hot cup of coffee, the elixir that fuels me on these trips.

We discover during dinner that the larder is getting low. Planning for food has gone pretty well. Ideally, we devour the last granola bar just as we cross the border into San Diego. Reviewing the menus of our meals, we discuss what could be added or subtracted for our next trip down here. Precut firewood tops my list as our wood has been a little too large to get a consistent fire going. I have a small hatchet, a relic of my older brother’s Scouting days, but this proves inadequate to split the larger pieces of wood. A greater variety of oatmeal flavors, macaroni and cheese, and peanut butter and jelly, old PBJ, tops our list of foodstuffs to bring more of next time.

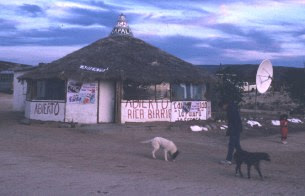

Over the years. Brandon and I have gone on lots of dive adventures all over the globe. The "hero pose" that you see in the image is one that we have come to call the "big friend, little friend" photo.